The forces impacting the legal services market are always in motion. That relentless inertia has been echoed in the market itself time and again – as new conditions and new challenges arise; the market reacts with a solution.

Now, the industry stands on the precipice of another necessary evolution.

Uniquely modern and long-developing market shifts have placed growing demands on in-house legal teams. New entrants to the market have targeted symptoms of these demands but failed to address the underlying problem.

It’s time for the legal industry to reframe its perspective and shift to solve a long-unserved problem.

In this whitepaper, we’ll explore where the legal marketplace sits today within the larger historical context, forces at play within the legal industry that make a market evolution particularly urgent, the previously unsolved problem of complex legal work at scale and the resulting need for Integrated Law™: a new category in the marketplace that combines expertise, efficiency, and alignment to unlock true potential.

Over 100 Years in the Making: Deconstructing the Legal Services Market

Like any deeply ingrained issue, the core problem that the legal services market needs to solve today began to form long before it became visible or urgent. To understand why the market is in need of progress, it’s important to first understand the market itself. How did we get here? What sparked the most notable shifts in the industry thus far? What’s next?

The industry in review

While the practice of law is ancient, the industry that evolved around it is a much more recent invention.

Large law firms and their full-service approach

The legal services industry as we know it today can, perhaps, be traced to the late 1800s when the concept of “large law firms” first emerged.

Just a few decades later, the “Cravath System” was invented. This established the pyramid-like organizational structure that many law firms still follow today, where partners are supported by multiple associates who hope to be promoted to partner.

Beyond changes to the size and structure of law firms, this period was marked by another important evolution for the legal industry: it was the first time lawyers were viewed as business advisers rather than strictly as advocates in the courtroom. In fact, Robert Swaine, a named partner in Cravath, wrote, “the great corporate lawyers of the day drew their reputations more from their abilities in the conference room and facility in drafting documents than from their persuasiveness before the courts.”

All of these developments helped usher in a period known fondly as the “Golden Era” for law firms. Throughout the mid-twentieth century, law firms developed close, long-standing relationships with corporate clients. Through the 1960s, many organizations relied entirely on one full-service law firm for all of their legal needs. This was due to the increasingly complex laws governing corporations – and the fact that these organizations lacked the in-house expertise to decipher those laws on their own.

Starting with the New Deal and continuing through the “rights revolution” thirty years later, complex legal requirements placed on corporations led to “information asymmetries” in business’ relationships with law firms – the complex nature of these requirements meant organizations needed support from law firms; investing in trusted, long-term relationships made corporations more comfortable with their reliance upon law firms. This also cultivated an environment where law firms held all the power.

But nothing gold can stay, and this gilded era for full-service law firms eventually faded.

The rise of in-house legal departments

By the 1980s (a decade marked by mergers and acquisitions), organizations were dealing with more transactional legal work than ever. It was complex, time-sensitive and seemingly unending. Perhaps most importantly, it had become too expensive to rely on outside firms to complete this work – particularly the recurring, business-as-usual (BAU) tasks. Basically, corporations needed a way to spend less while managing more work.

To solve this problem, Jack Welch, CEO of GE, tasked Ben Heineman, GEs then General Counsel, with creating a legal department that rivaled the best outside firm. It was 1987, and although GCs and in-house legal departments existed in some form, Heineman is generally credited with revolutionizing them into the roles we recognize today.

Heineman ended GE’s long-standing relationships with outside firms. He hired top legal talent. The information asymmetries that had marked the Golden Era were eliminated. GE’s in-house team handled much of the work that was once sent to outside firms; when outside support was needed, the legal department sourced and oversaw it. As they say, the rest is history: by 2006 when he retired, Heineman had built an elite legal department of 1,000 lawyers, larger than all but the largest global law firms.

GE’s endeavor was a success. Other businesses followed suit. Full-service law firms no longer served as the sole trusted business advisors – that role now fell to in-house legal teams. Instead, law firms were tapped for highly specialized tasks that couldn’t be completed in-house. What’s more, corporations began engaging with multiple outside firms – creating panels of preferred providers – a far cry from the tight-knit relationships of the Golden Era.

The growing trend of in-house legal departments placed pressure on law firms to reduce costs, stick to billing guidelines and increase productivity. But this forced accountability has caused friction. As recently as 2015, 72% of law firm leaders said the pace of change will continue to increase despite 65% of partners showing resistance to change efforts.

The increased in-house handling of legal work that has occurred over the last 35 years could be explained as a reaction to the industry in the Golden Era – indeed, Jack Welch’s goal in 1987 was to cut GE’s legal costs. But in reality, Welch’s cost-cutting objectives speak to broader mounting pressure businesses have felt for decades, and it’s only grown more acute through the rise of in-house legal teams, the development of New Law and into the present day.

An era of urgency: the three key issues begging change

By the late 1980s when the concept of a robust in-house legal department gained steam, organizations had realized it was cost prohibitive to outsource their recurring BAU work – those complex, urgent tasks that grow more frequent as the business thrives.

Today, this fact hasn’t changed. But plenty of other things have.

The challenges that first led organizations to bring legal work in-house still exist, but now, legal departments’ workloads are growing at a noticeable (and largely unmanageable) rate – both in scale and complexity. The need for high-level advice from GCs and In-house lawyers (IHL) is multiplying. The industry has responded with cost-effective New Law providers focused on efficiency. Meanwhile, outside law firms grow more expensive and in-house teams don’t grow at all.

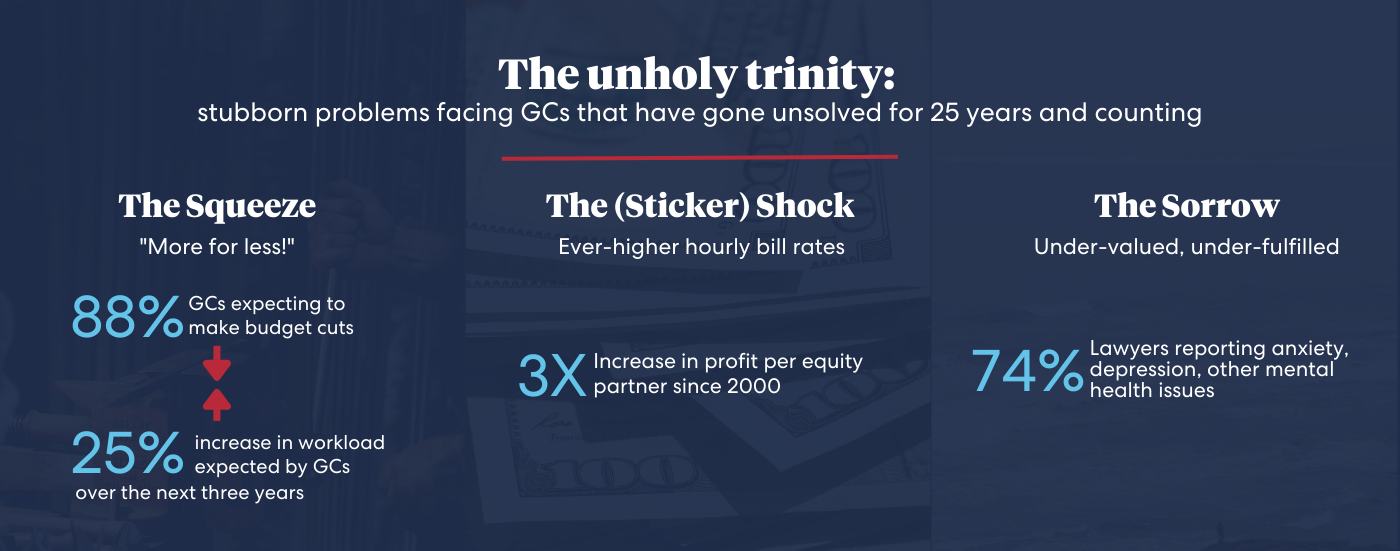

These factors, which explain the sense of urgency now felt for continued evolution in the legal services market can be broken down into three key issues: squeeze (the pressure on in-house legal teams to do more with less), sticker shock (the rising cost of external law firms), and sorrow (the human emotion underscoring, resulting from and contributing to these other elements).

The competing squeeze: bigger and more complex workloads, stagnant budgets

Anecdotally, it’s widely accepted that IHL workloads have grown in recent years. But have they really? And if so – why?

According to the 2021 Corporate In-Housing Survey, 71% of IHL saw increased workloads during the pandemic; 54% believe that pandemic-related changes are here to stay. Yet another survey projects that workloads will rise by 25% over the next three years, with headcount expected to grow by a comparatively measly 3%.

So, workloads have, indeed, increased markedly in the last few years. The question of why is a complicated one.

Unpacking the workload problem

One clear culprit for the growing burden felt by in-house legal teams is budget. According to a Thomson Reuters survey, 29% of in-house departments cut legal spending in 2020. In 2021, a whopping 88% of GCs planned to cut their budgets due to pressure from the Board and C-Suite. Reducing costs and handling budget restrictions were ranked as two top priorities by in-house teams in a 2021 survey. With fewer resources, IHL have no choice but to take on additional work themselves.

Another explanation—one that is perhaps not wholly divorced from budget—is staffing shortage. Shrinking budgets and a volatile labor market may certainly account for some of the increased workload that IHL are experiencing, but even if the workload itself remained exactly the same, these factors would cause it to feel greater.

We could explain the expanding workloads of IHL this way — as a mere trick of perception — if it were only an issue of slashed budgets and unstable staffing. But it’s not.

Nearly 80% of in-house teams are looking for ways to manage a greater workload with the same number of people. In other words, even teams whose headcount has remained stable are grappling with more work.

This pressure to do more with less is nothing new. Remember, it was a key source of inspiration for revolutionizing legal departments in the first place. So, if this squeeze in and of itself isn’t novel, why does it feel so much more urgent and burdensome now?

Macrotrends spell new challenges

Prior to the pandemic, a long list of macro-environmental forces had already begun changing the world for businesses at large. Among the most glaring of these forces are:

- Rapid technological advancements

- Ease of access to information

- Climate change (and resulting resource insecurity)

- Socioeconomic instability and polarization

Through the lens of business (and specifically In-house Law), these broad drivers of change create the need to examine specific shifts and potential threats like:

- Evolving expectations for corporate mission and responsibility (particularly related to ESG and DEI)

- New geographies due to increasing globalization at the same time as increasingly protectionist policies in geographies making working across these complex

- Digital transformation

- Increasing regulatory complexity

- New currency considerations (both in terms of fluctuation and the use of cryptocurrency)

- Business models capable of adapting to a rapidly changing environment

- Risks related to the frequently litigious nature of periods of volatility (like that of the pandemic or a recession)

- Supply chain issues resulting from political unrest, resource scarcity and economic factors

The pandemic catalyzed some of these factors and added a few of its own, but others were in motion well before Covid-19 became an omnipresent concern in the collective global consciousness. So, IHL are now forced to manage an increasingly complex list of priorities made tougher yet by stagnant budgets and slow-to-grow staff.

While businesses once focused almost exclusively on economic-based metrics of success, the scope of success has now widened at the behest of a variety of market actors – customers want to connect with a business’ mission and culture, regulators want more stable businesses. And indeed, even economic metrics of success (still undeniably vital to any sustainable business) are inextricably linked to other, new considerations.

For example, businesses at a mature stage of their digital transformation enjoy higher revenue growth than industry averages; a mature digital transformation also (ideally) lends itself to compliance with increasingly complex regulatory and privacy concerns thanks to healthier data hygiene.

Essentially, none of these elements exists in a vacuum. They’re interconnected and integral to the business, meaning they not only create new advisory burdens, but also facilitate a more complex BAU workload.

The sticker shock of specialist expertise

The growing complexity and scale of BAU work puts greater pressure on in-house legal teams, but outsourcing to law firms is, perhaps, less cost effective than ever.

A junior associate now bills hourly what a partner did ten years ago.

In late 2021, a survey indicated that legal departments' outside counsel spend remained flat despite the fact that mergers & acquisitions – a type of work for which many organizations partner with outside law firms – is one of the top five anticipated growth areas. This may speak to the fact that the sticker shock of engaging with outside counsel has become untenable.

Once again, the fact that outside law firms are too expensive to engage for routine work isn’t exactly a revelation; it’s been understood for decades. But the sharp rise in hourly billing rates we’ve observed over the last 15 years speaks to the urgency of the problem legal departments are facing today. After all, if outside counsel was too expensive before these increases, they’re certainly not a budget-friendly solution today, and the reality is that in-house legal teams simply can’t handle everything themselves.

The human element: sorrow and its impact on in-house morale

An unhappy complement to (or result of) the squeeze and sticker shock felt by in-house legal teams is something equally damaging: sorrow. Burnout, a lack of balance and an inability to focus on the work to which they’re best aligned all contribute to this problem.

Out of the office but on the clock

According to a flash poll by the Association of Corporate Counsel in June of 2020, more than 50% of respondents felt they were working more hours from home, but about 50% also said they were able to easily “switch off” from work when it was time to relax.

Fast forward two years and the Bloomberg Law Attorney Workload and Hours Survey found that respondents felt burnt out 52% of the time – the highest reported percentage since the survey’s inception. What’s more, 72% of survey respondents now said they had trouble disconnecting from work.

Perhaps this helps explain a marked rise in attrition. Law wasn’t immune to the Great Resignation that sent so many employees in search of greener pastures; attrition rates in the industry increased by more than 50% between 2020 and 2021.

It’s worth noting that the industry-wide burnout trend is particularly pervasive among IHL. A 2021 Gartner survey of corporate lawyers found that 54% are feeling some level of exhaustion. Within that group, 86% were looking to leave their jobs and 95% frequently delayed, scoped down or killed projects altogether.

But what exactly does that mean?

In-house legal teams concentrate on contracts more than any other field. This type of recurring transactional work is urgent; it has an immediate commercial impact and requires interaction with business stakeholders. It’s also some of the most visible work in-house teams complete. This work isn’t going anywhere – the projects that exhausted IHL are scoping down or killing likely don’t fall into this category.

After all, contracting (and other recurring transactional work) is only one piece of the puzzle for IHL. In fact, 80% of in-house teams say providing proactive legal advice to the business is a top priority – this comes as little surprise given the evolving concerns facing businesses. High-level advisory work is clearly top of mind, but it rarely reaches the top of the to-do list thanks to the ever-increasing flow and complexity of BAU work.

The apparent disconnect begs the question: how can GCs and IHL negotiate these conflicting priorities? As burnout proliferates and recurring transactional work like contracting grows a new kind of solution is necessary to enable focus on the high-level advisory work that so many teams rank as a priority.

Uncovering the core problem to solve the uncovered gap

The unmanageable workloads of in-house teams, the rising prices of outside firms (making them a cost prohibitive option for recurring work) and the resulting burnout felt by legal departments lead to a clear conclusion: work must be taken off in-house teams’ plates by non-law firm service providers.

Unpacking innovation in the legal industry

An innovation gains the descriptor simply by disrupting something established. By definition, the rise of in-house legal departments was innovative. And so, too, was the rise of “New Law” providers over the course of the last decade, including Alternative Legal Service Providers (ALSPs), Legal Tech, Legal Process Outsourcing (LPO) firms and more.

But for most people, the word “innovation” implies more than just disruption – it implies progress. So, have these waves of new entrants made progress toward solving the problems with which in-house legal teams are grappling?

Yes and no.

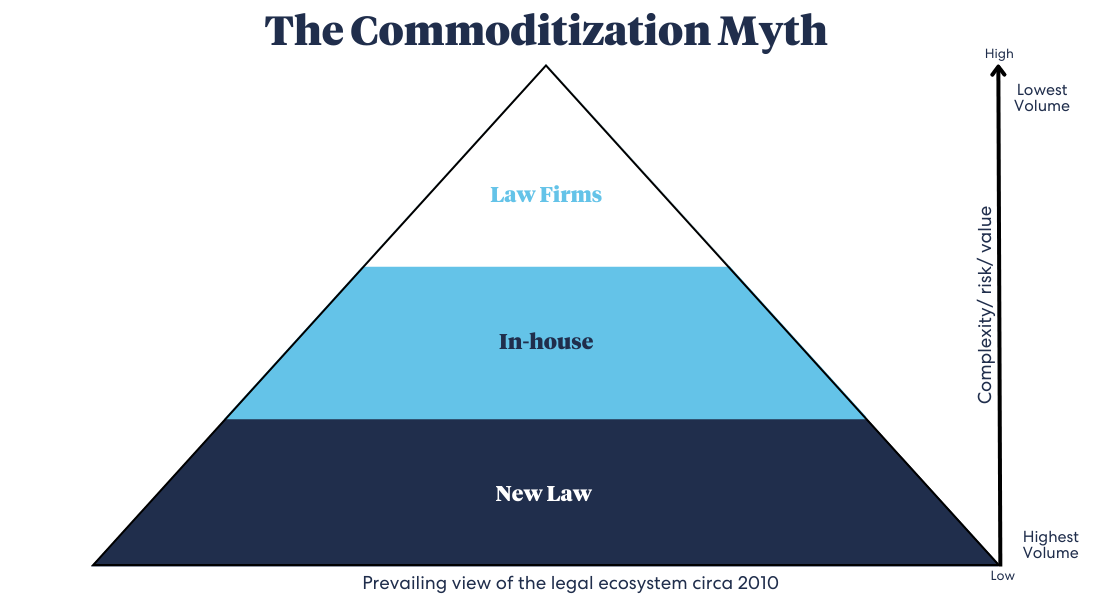

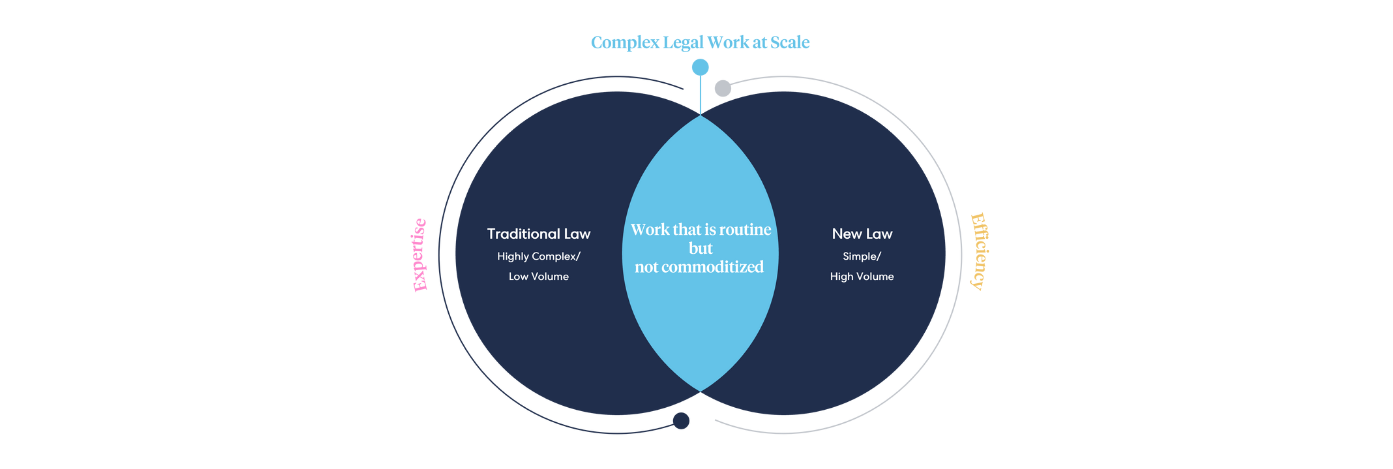

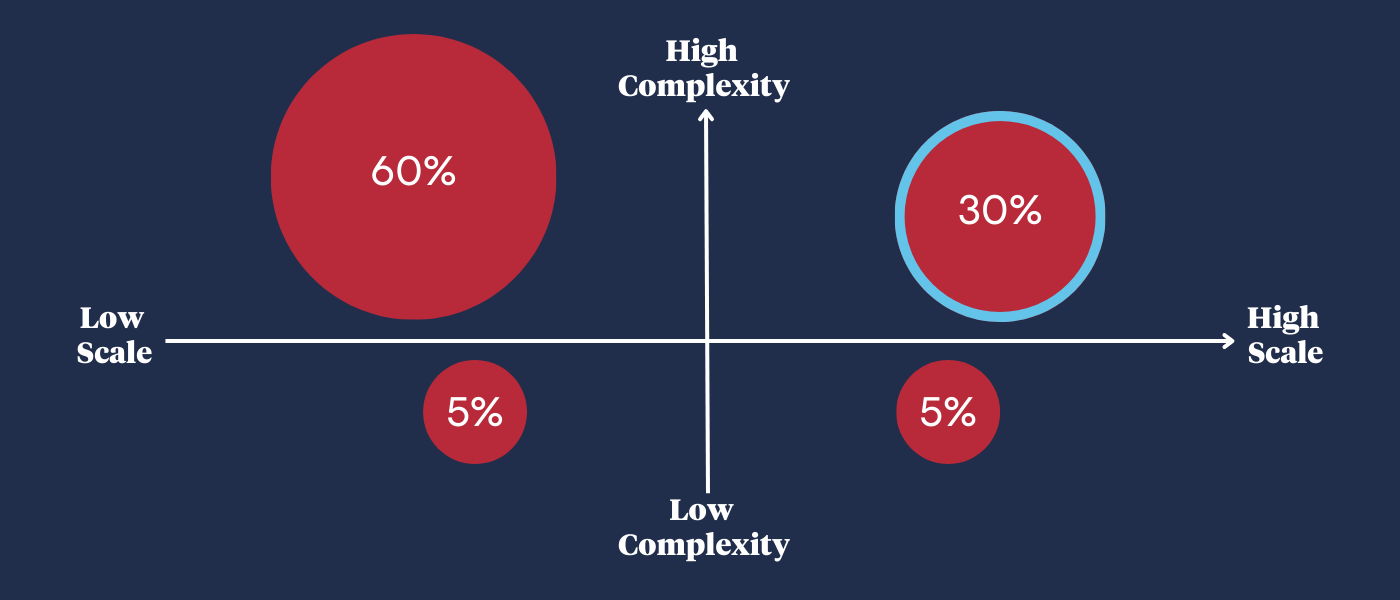

To understand that answer, it’s important to understand the prevailing view of the legal ecosystem circa 2010 – a viewpoint from which New Law providers were created in a bid to boost efficiency without inflating budgets following the Financial Crisis. At this time, the accepted belief system asserted that complex work is rare and simple work is abundant.

This formed the premise upon which New Law was built.

Since the simplest legal tasks (believed to be the highest in volume) require less expertise, New Law providers could handle them efficiently and cost effectively. On the other end of the spectrum, the especially complex tasks (believed to be the rarest) require a high degree of expertise and could be reserved for outside law firms.

The work left in the middle would fall to in-house legal teams, but New Law providers would ostensibly offload the bulk of the urgent tasks.

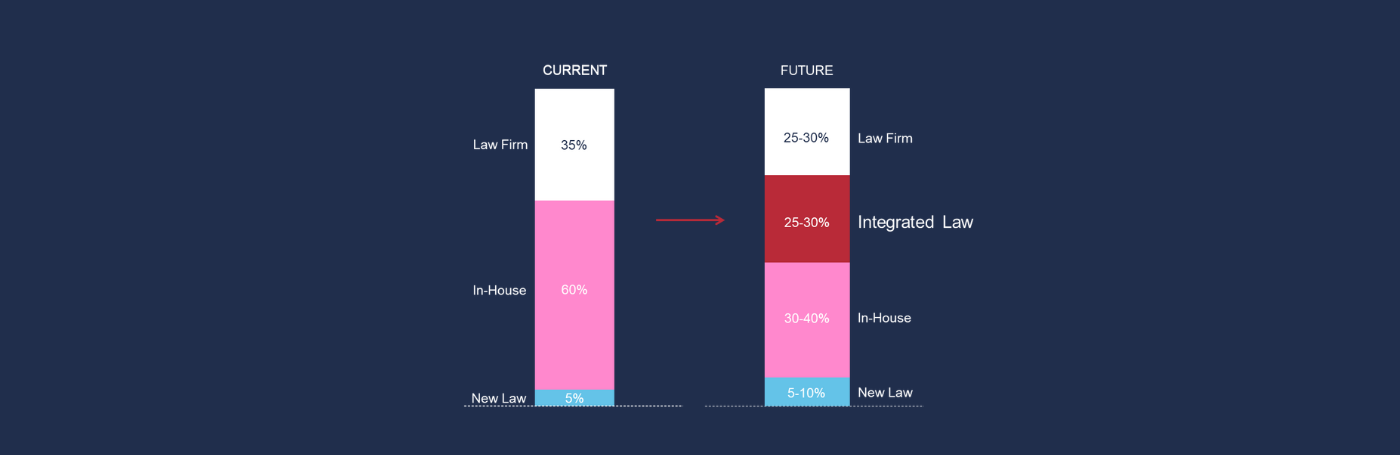

Certain elements of New Law’s promise have come to fruition. It’s true that New Law has taken up high volume, low complexity tasks (like e-discovery) and gained market share – 79% of law firms and 71% of corporations respectively now say they use ALPS, and the market has a compound annual growth rate of 15%.

Still, less than 5% of legal departments’ annual spend is with alternative providers on this type of work. On its own, this isn’t wholly surprising – cost effectiveness is a main benefit of New Law providers. But coupled with what we know about growing in-house workloads, rampant burnout, rising law firm profits and the growing complexity of BAU work, low legal spend on alternative providers points to another explanation.

The past decade’s innovation efforts in the legal industry have been largely misdirected.

The premise that simple work is abundant and complex is rare simply isn’t true. In reality, in-house legal teams are mostly bogged down by complex transactional work – the urgent BAU tasks that can’t be outsourced and can’t be ignored – and not simple, low-complexity work.

Moreover, legal work doesn’t exist on a sliding scale from “less complex” to “more complex” at all. Instead, it often features different flavors of complexity, each of which requires unique capabilities. So, although New Law providers are naturally aligned to tasks featuring scale complexity (where efficiency and tech enablement are vital), they generally aren’t equipped to handle work that is complex in other ways.

The root issue of mixed-complexity work

Simply put, legal innovation has largely failed to alleviate the pressure felt by GCs and IHL thus far because it hasn’t targeted the work that’s burying them.

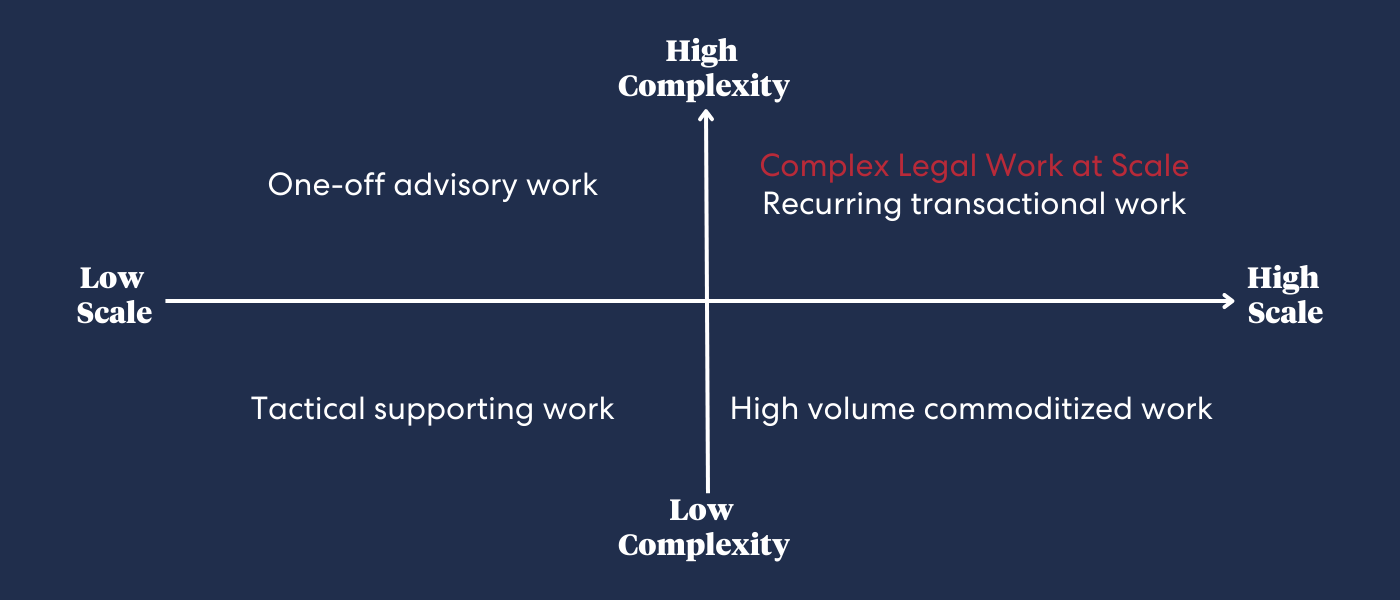

The misconception that legal departments are drowning in an avalanche of simple tasks has misdirected innovation because it has oversimplified the core problem. The reality is that virtually all the work handled by in-house legal teams is complex in at least one of three ways:

- Scale Complexity: work that is complex due to its volume.

- Legal Complexity: work that is complex because it requires specialized expertise.

- Systemic Complexity: work that is complex because it requires an understanding of (and alignment with) the organization’s culture, strategies, systems and processes.

When New Law first rose to prominence around 2010, the assumption was that most work fit squarely within the scale complexity box. But a large chunk of work doesn’t fit wholly within any of these categories of complexity – it features elements of each.

This mixed-complexity work that requires expertise and business alignment as well as scale accounts for the true drain on legal departments. So, complex legal work at scale is the problem, but what is the solution?

Integrated Law™: A Market Evolution

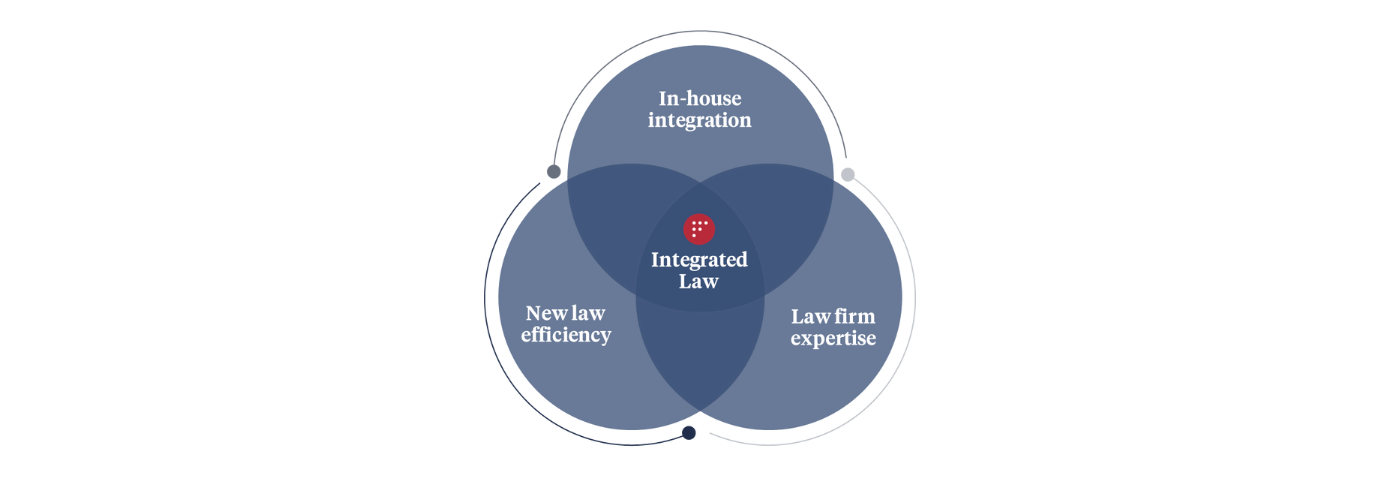

The industry has progressed markedly since the late 19th century when law firms first emerged in earnest. In order to tackle complex legal work at scale (CLWAS), it must continue to evolve. Integrated Law combines the strengths of existing providers, establishing the necessary mix of capabilities to finally cover the unattended gap in the market.

Understanding the existing legal services market

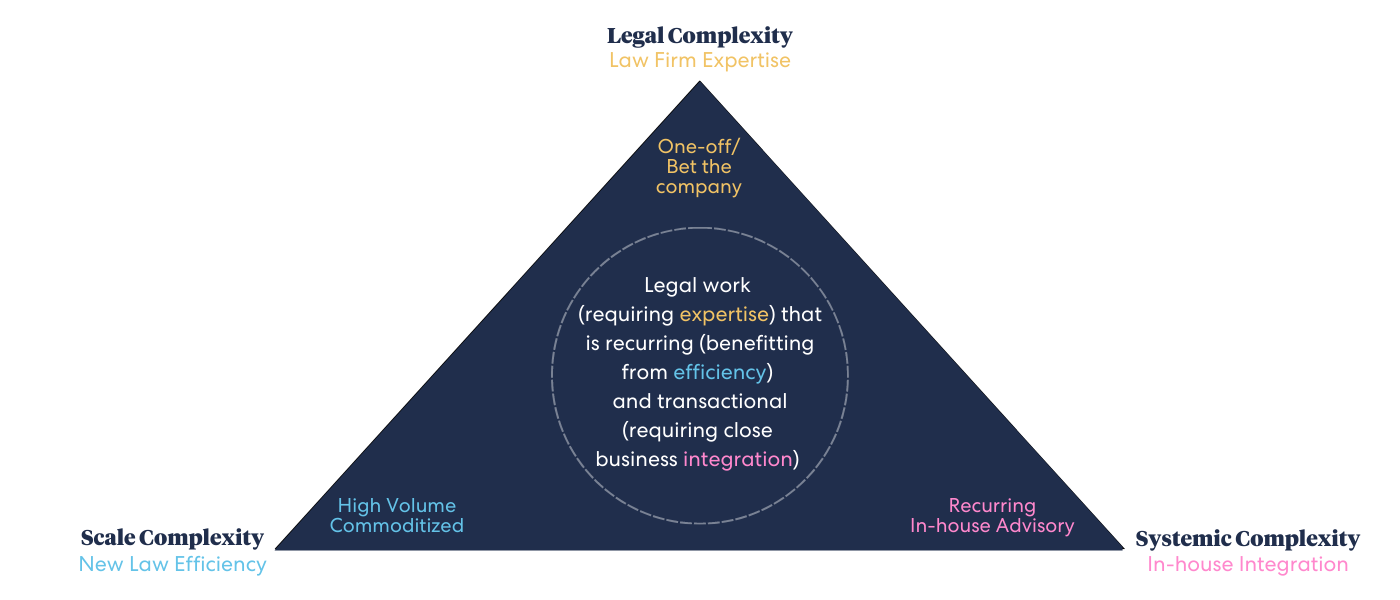

Prior to Integrated Law, existing players in the legal industry could effectively be grouped into three categories: Traditional Law (law firms), New Law (legal tech, LPOs, ALSPs) and In-house Law (GCs and legal departments). Though continued innovation is needed to handle CLWAS, each of these types of providers is uniquely suited to a specific flavor of complexity.

Traditional Law and legal complexity

Given the history of law firms and the fact that specialist expertise is the top reason cited for engaging with an outside law firm, it should come as little surprise that law firms are best aligned to work marked by legal complexity.

Traditional Law offers the kind of expertise that inspires trust during major, bet the company transactions and advisory work. This might include:

- Novel regulatory compliance

- Acquisitions that trigger anti-trust law

- Company restructuring

Because of their cost and expertise, these providers are best suited to work that is high in legal complexity and low in scale complexity.

New Law and scale complexity

As evidenced by their growing market and increasingly mainstream adoption, New Law providers are clearly doing something right. That something is the high-volume commoditized work that features scale complexity.

Legal tech proves hugely valuable in use cases like e-discovery and M&A where standards and specialist knowledge and judgement can be more readily coded against a massive bulk of data – but these cases are relatively narrow. New Law’s answer for work that can’t be handled by Software as a Service (SaaS) solutions comes in the form of ALSPs, LPOs and similar providers. Because they bring significantly less expertise to the table, this type of outsourcing is less expensive and more efficient than outside law firms, making New Law best aligned to work like:

- Legal transcription

- Legal coding

- Document management

- Billing

Their tech-enabled efficiency means New Law providers are best suited for work that is high in scale complexity and low in legal complexity.

In-house Law and systemic complexity

The third dimension of complexity relates to organization-specific nuances – business strategies, established systems and processes, overarching culture – considerations that In-house Law is uniquely equipped to manage.

Their proximity to and alignment with the business means in-house legal teams are best suited to handle high-level advisory work such as:

- Advising on new products and markets

- Approaching complex external disputes

- Developing policies to balance legal and commercial interests in transactions

In-house teams may be capable of tackling work that is relatively high in legal and scale complexity as well, but systemic complexity is the area where they fit most naturally and unlock their highest potential.

Reaching across complexity silos

If these three dimensions of complexity – scale, legal and systemic – existed wholly separately, and if the squeeze, sticker shock and sorrow felt by legal departments had not grown so urgent, then perhaps the market could have hovered at its last visible evolution (the one that gave us New Law around 2010).

But as we know, everyday work is becoming more complex, and it’s happening in more ways than one. More than ever before, BAU work features multidimensional complexity; CLWAS exists at the intersection of the three complexity dimensions to which existing providers are naturally aligned.

This recurring transactional work is too high in scale for Traditional Law and too high in legal complexity for New Law. In-house legal teams have attempted to handle it, but they’re already spread too thin and grappling with low morale – focusing on this urgent work crowds out the important, systemically complex work where they thrive.

So, the next evolution in the legal services market must intentionally tackle CLWAS. Integrated Law does just that.

Integrated Law™ in practice

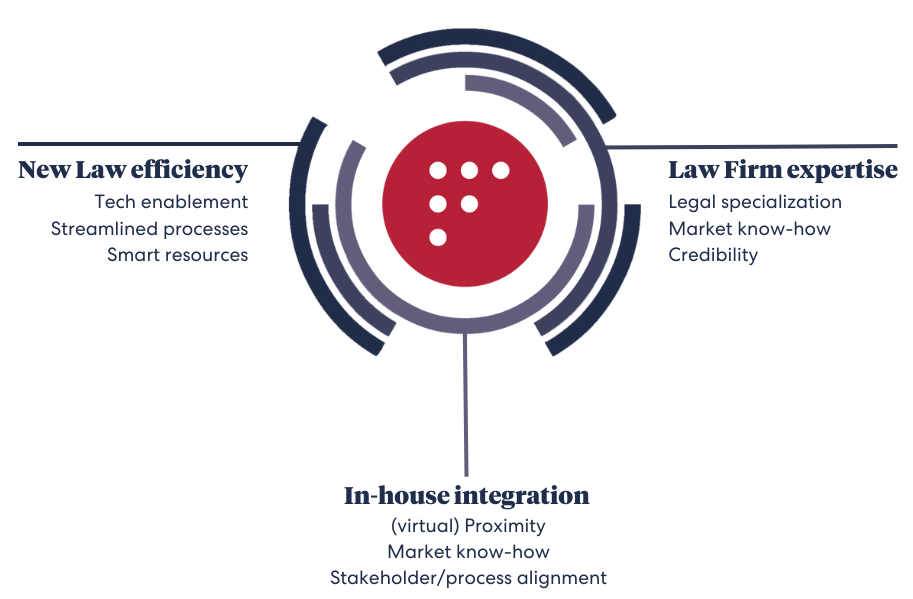

Integrated Law combines the expertise of Traditional Law, the efficiency of New Law and the close business alignment of In-house Law. This is achieved through both talent and organizational structure.

In terms of talent, Integrated Law providers utilize a mix of lawyers, subject matter experts (SMEs), contract analysts, process quality professionals, project managers, technologists and more. In addition to diverse skillsets, Integrated Law teams need diverse experience – when Traditional Law, In-house Law and New Law backgrounds are all represented, it ensures the proper mix of capabilities.

The way those capabilities are applied is where Integrated Law gets its name. Providers in this category deliver work inside the client ecosystem, aligned to business needs, goals and operating models. Day to day, this means they operate within client systems and function, for all practical purposes as a part of the in-house legal team, albeit one with easy access to additional resources and expertise.

Teams aren’t outsourced, they’re embedded – by integrating within a business and taking ownership and accountability, Integrated Law providers foster long-term relationships where the line between “client” and “provider” grow blurry, and eventually disappear entirely.

In its mature state, Integrated Law reorders the legal marketplace around highest-best use. Instead of steering businesses away from other categories, Integrated Law creates a clearer delineation of how and when to use the different providers in alignment with the type of complexity to which they’re best suited:

- Traditional Law: Bet the company, one-off transactional and advisory work

- New Law: Efficiency-driven, high-volume commoditized work

- In-house Law: Recuring advisory work that balances business objectives with legal risk

- Integrated Law: Complex Legal Work at Scale (recurring transactional work)

Integrated Law frees IHL from the ever-increasing burden of transactional work and allows them to focus on core advisory work – solving business problems, managing risks and navigating strategies. Once this core problem is resolved, initiatives like tech solutions and legal ops projects can be explored in earnest.

By addressing the underlying problem in the legal services market, made more urgent by the modern world, Integrated Law builds a bridge between reality and objective so legal departments are no longer left to drown in a river of complex legal work. With expertise, efficiency and alignment, Integrated Law solutions augment potential and allow in-house teams to reimagine their roles.

The Integrated Law™ Impact

We’ve established that CLWAS is a problem, but exactly how big is that problem? And what are the potential benefits of resolving it? Let’s explore some estimates and case studies to bring the conversation further into the real world.

Across the Fortune Global 500, Complex Legal Work at Scale represents an estimated $56,700,000,000 of legal spend. It might seem counterintuitive to suggest that organizations spend more on CLWAS given this period of belt tightening, but Integrated Law providers help decrease costs and build sustainable results while freeing in-house teams to perform high-level advisory work that would otherwise go untouched.

By the numbers: breaking down results

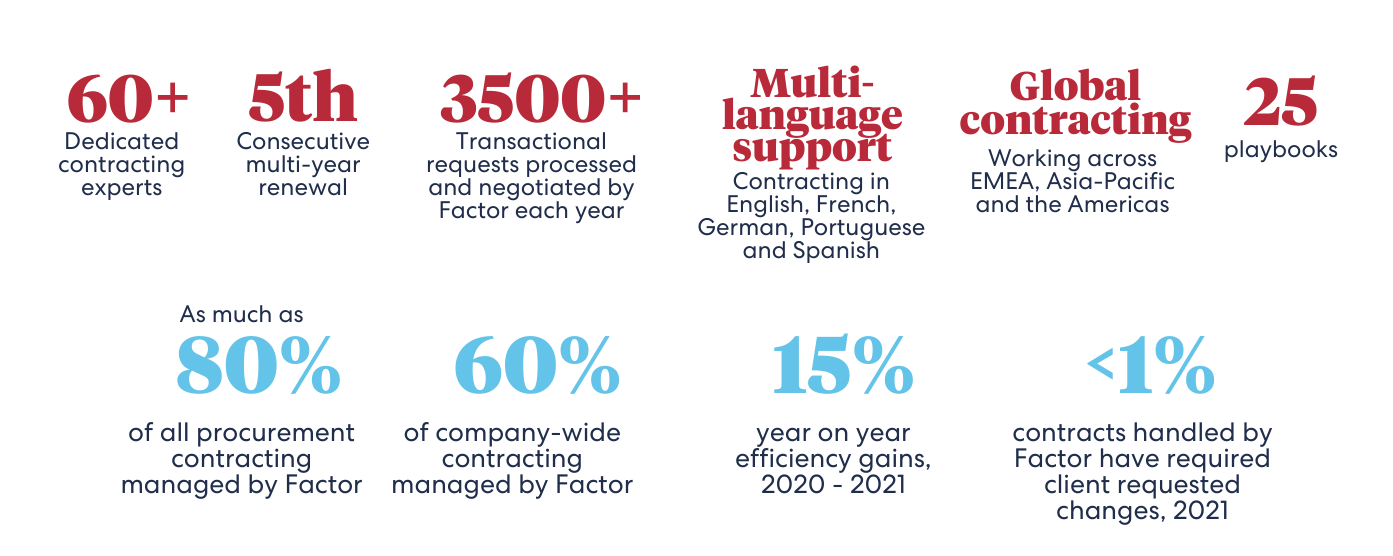

As a part of the Integrated Law category, Factor can attest to the long-term value of this approach. But numbers speak louder than words, so we’ll let clients’ results do the talking.

Case Studies

Global Telecommunications Business

Before working with Factor, a global telecommunications business handled commercial contracting through the in-house legal team with the help of external legal counsel. Template rationalization was done, but the negotiation guidance had been drafted in an ad hoc, decentralized way – it was incomplete, inconsistent and (often) outdated. Templates were stored in multiple places with no oversight and governance.

Our client wanted to consolidate contracting support and work with a strategic partner that could provide legal expertise, a technology-enabled consistent process, high-quality outputs, and associated data and insights. They also wanted to work with a team that would feel like an extension of their own, aligned with their values and way of working. The client engaged Factor in 2013, and today (after multiple renewals) we are fully embedded with their legal and business teams, with activities ranging from routine queries on contract interpretation to complex negotiation of high-value contracts. We support a broad spectrum of commercial legal work, including purchasing, licensing, sponsorship and enterprise customer agreements across all of our client’s customer facing units.

Multinational Healthcare Company

A multinational healthcare company needed to set up a centralized procurement contracting function. At the time, the team handled 4,500+ contract requests every year. In addition to the challenge presented by a large volume of contracts, the contracting process lacked central oversight and standardization, data capture and reporting.

In 2015, our engagement with this client began. Today, we handle intake, triage, drafting, negotiation and execution of procurement contracts, delivering contracting best practices as well as robust operational data capture and reporting to inform the process and business decisions. We deliver a streamlined contracting process as we continue to identify and realize efficiencies.

Biotechnology Company

A biotechnology company needed to increase efficiency and create a long-term solution for the target cycle time of their clinical trial agreements. Their legal team did not have effective templates and playbooks, affecting the quality and speed of their output.

To solve this problem, Factor is developing prescriptive and illustrative playbooks to enable negotiation directly with sites on client and third-party paper, reducing overall negotiation cycle time. Our team created a template analysis workbook and risk provision matrix as part of Factor’s methodology and as a best practice guide across all regions. Our partnership has now expanded; an additional Factor managed services team is streamlining the clinical contracting process to achieve shorter contract lifecycles and faster execution, drafting, negotiating and preparation of final drafts.

Factor was born to handle Complex Legal Work at Scale (CLWAS) and is now defining the Integrated Law category.

Our workforce of 600+ globally is sophisticated, experienced and designed specifically for CLWAS. Over 50% of Factorians are lawyers; the majority of our workforce is legally qualified with an average of six years of experience, and we’re proud to have more experienced SMEs than any other competitor.

In line with our aim of mixing expertise, efficiency and alignment, our team brings a curated mix of law firm, in-house and New Law experience.

Our assertion that Integrated Law is a market necessity comes from hands-on experience. We have 10+ years of focused experience and learnings from contracting work – the most frequent case of CLWAS.

In an age marked by heavy workloads, widespread burnout and volatile economic conditions, an Integrated Law solution isn’t just nice to have – it's imperative to success. To learn how Integrated Law™ could be applied in your organization, contact us.